In previous articles, we discussed the reasons to consider investing in a condition monitoring system (part 1), the financial impact of a maintenance policy without a condition monitoring system (part 2), and the financial impact of a maintenance policy with a condition monitoring system (part 3). This article focuses on the ultimate goal of any investment: the investment must ultimately generate or save money. This can be calculated using several methods, which together provide a clear insight into the investment. Key decision-making methods are discussed below.

All figures in this article are fictitious and purely indicative; actual costs and savings may vary, and no rights can be derived from this information.

Payback period (PP)

A crucial factor: within what timeframe will the investment be recouped? A company may set an ultimatum for when the investment must be recouped. The payback period is relatively easy to determine, but it does not account for inflation and assumes even payback over time. It can be calculated as follows (see Table 1):

- costs (c) / savings (s) = payback period (PP).

Return (R)

Closely related to the payback period, this also does not account for inflation. It can be calculated as follows (see Table 1):

- savings (s) / costs (c) = return (R)

Return on Investment (ROI)

This method is more accurate than the previous methods as it accounts for depreciation and disposal costs at the end of the equipment’s lifecycle. The total benefit over a specified period is also included. ROI consists of three calculations (see Table 1):

- (costs (c) – residual value (rv)) / number of years (y) = annual costs (AC)

- (revenue – total costs¹ (tc)) / number of years (y) = annual cost benefit (ACB)

- (annual cost benefit (ACB) / annual costs (AC) * 100%) – 100% = annual ROI (ROI)

¹Adjusted for residual scrap value (e.g., €10,000 in this example)

Net Present Value (NPV)

More accurate than the methods above, as it includes the entire lifespan of the equipment, considers inflation, and accounts for various cost and revenue streams throughout the equipment’s life. This method is more complex than the previous ones. First, the Present Value (PV) must be calculated (see Table 1). Then the Net Present Value (NPV) is calculated (see Table 1):

- Revenue (r) / (1 + interest (i)²) = Present Value (PV)

- Present Value (PV) – total costs* (tc) = Net Present Value (NPV

*Adjusted for residual scrap value (e.g., €10,000 in this example)

Cost-Benefit Ratio (CBR)

The Cost-Benefit Ratio (CBR) considers the size of the required financial investment. It is possible for the NPV of two competing projects to be the same while the project costs differ significantly. The higher the CBR, the better. It can be calculated as follows:

total costs* (tc) + Net Present Value (NPV) / total costs* (tc) = Cost-Benefit Ratio (CBR)

*Adjusted for residual scrap value (e.g., €10,000 in this example)

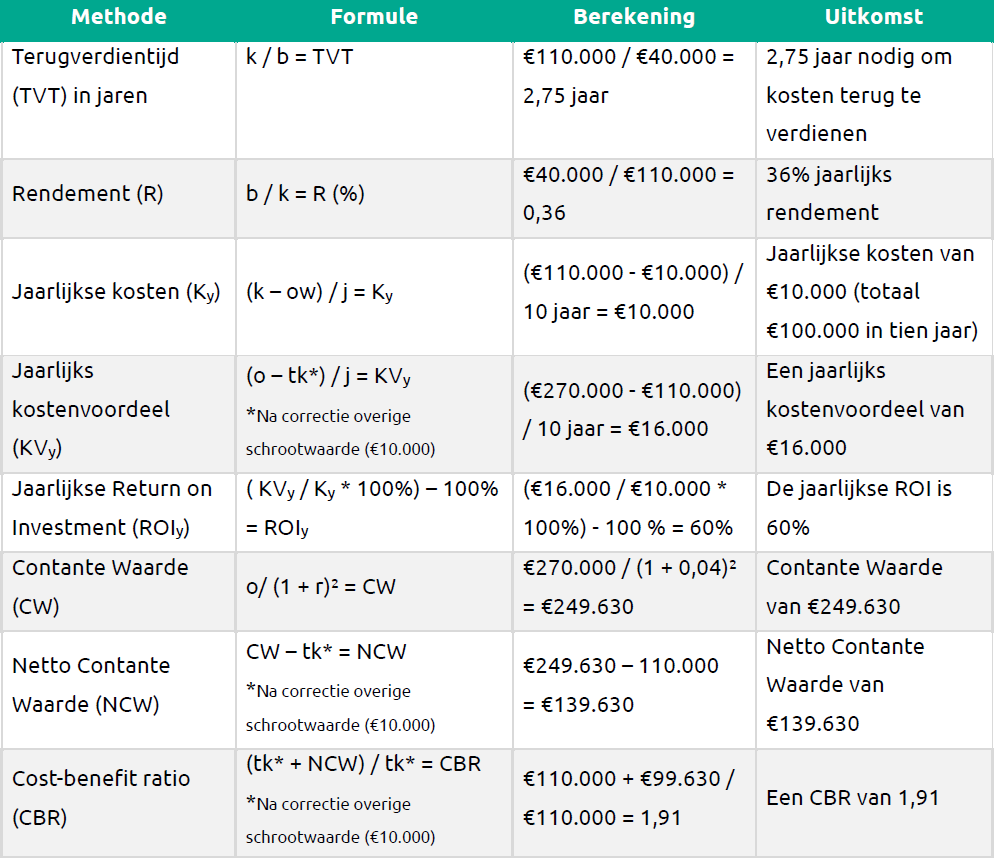

Table 1. Overview of example calculations.

Explanation of Table 1: The above table provides relevant calculations for financially justifying the purchase of a condition monitoring system. Note that all figures are fictitious and are purely for illustrative purposes. The abbreviations in the formulas are described earlier in the text, but a brief overview is provided below (Table 2):

Table 2. Abbreviations used in formulas